When Mark Seddon and I started to write our book about Jeremy Corbyn and Labour, we were advised to keep away from anti-Semitism. Anything we wrote would be misrepresented, we were told; and it has been.

But I knew we had to research it properly, because I live in Finchley. In the council elections in May, Labour made gains nationally, but Barnet went from a hung council to a Conservative majority of thirteen seats.

The Conservatives owed their victory entirely to the perception that the Labour Party is riddled with anti-Semitism.

So is it? Or is it all a Tory ramp, as some Corbynites claim?

Our conclusion: neither of these things is true.

It is true that Corbyn, in a 35-year political career, has frequently failed to negotiate the minefield of what you can and cannot say about Israel without sounding anti-Semitic, and has said several things which are now coming back to haunt him.

It’s true that he’s reacted badly to the accusation, by keeping his head down and hoping it would go away. Corbyn could have made the issue his own, and become the solution, not the problem, as the former Board of Deputies of British Jews President Jonathan Arkush told him he should.

It’s also true that anti-Semitism is back in Europe, and in Britain. The first half of 2016 saw an 11 per cent rise in anti-Semitic incidents in Britain.

But it’s also true that the Board of Deputies has not been willing to hold the right and the Conservatives to the same standards as those to which they rightly seek to hold Labour and the left.

They did not, at any time in the five years of his leadership (2010-2015), make any attempt to defend Ed Miliband against anti-Semitic attacks. Even the dreadful Mail article on Miliband’s father merited not even a mild protest to the editor. The regular use of the bacon sandwich image of Miliband, with its sneering subtext; the use of the phrase 'North London metropolitan elite' as a code for Jews (it’s never used about Corbyn, though he’s a north Londoner too); all went unchallenged.

The growing Conservative Party links with anti-Semitic parties in Eastern Europe have gone virtually unnoticed; the Board of Deputies shows no appetite for holding the party to account for them.

As Deborah Lipstadt, the pre-eminent historian on Holocaust denial, has said, “It’s been so convenient for people to beat up on the left, but you can’t ignore what’s coming from the right.”

And yet, come the 2015 election, Labour canvassers in Finchley found, not anger at anti-Semitic attacks on Labour’s leader, but a belief that anti-Semitism was Labour’s virus. Yet Labour was offering the first Jewish Prime Minister since Disraeli, and a Jewish MP.

If Mrs May’s chaotic Brexit were to triumph because Labour is seen as racist, that would be a horrible wrenching irony that everyone would understand.

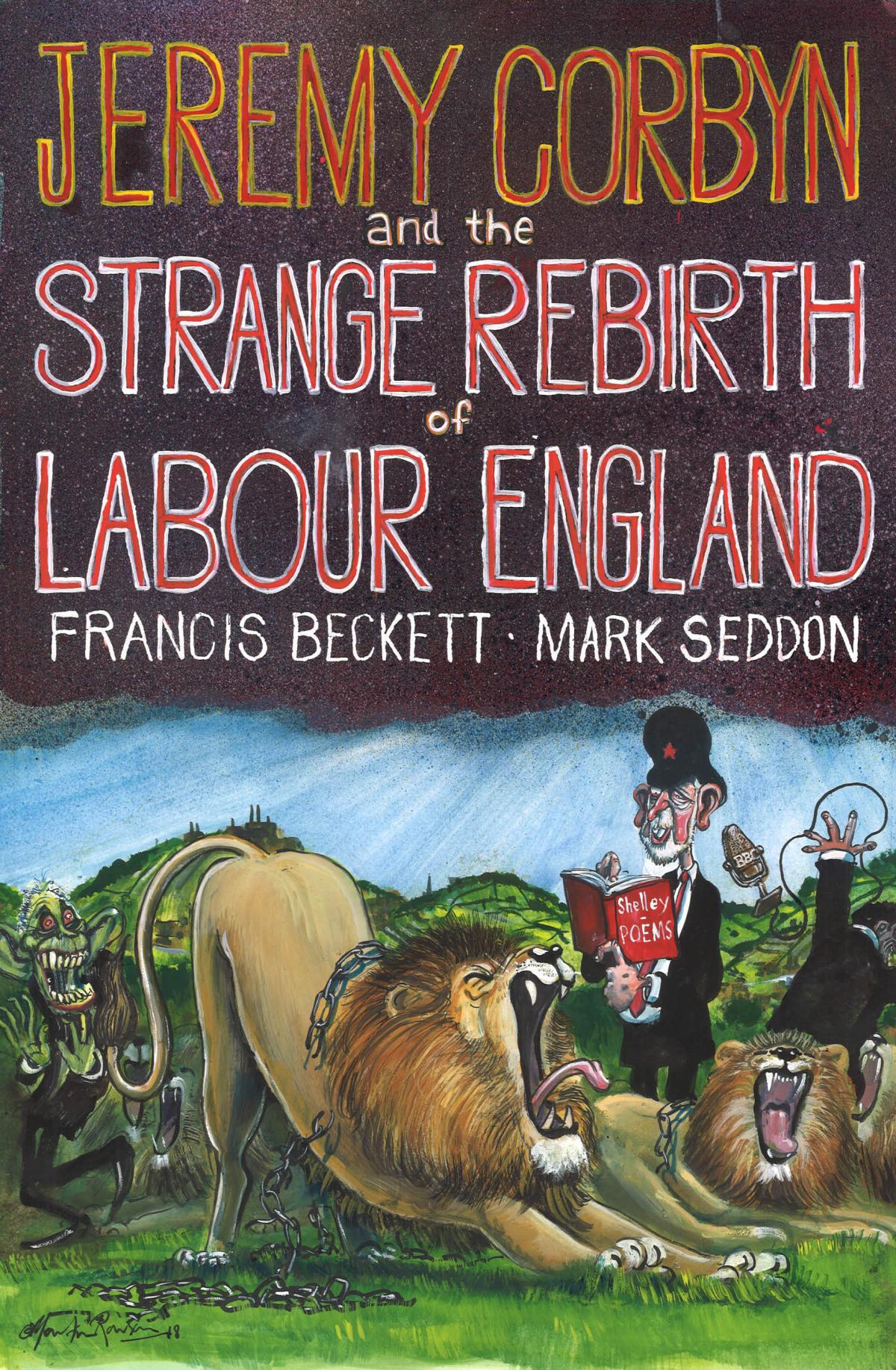

• Jeremy Corbyn and the Strange Rebirth of Labour England by Francis Beckett and Mark Seddon is published this month by Biteback.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel