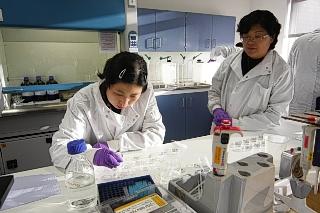

Science as we know it is changing and this week Middlesex University showed Elizabeth Pears how an image overhaul puts it at the forefront of teaching.

At the start of the academic year Middlesex University opened the doors of its £35 million Hatchcroft building at the Hendon campus, signifying a shift from the past to the future.

The three-storey building is the new home of biomedical research — the study of health and disease in the human body — and teaching laboratories, following the closure of the Ponders End campus in Enfield.

While the west wing is dedicated to biomedical research, the eastern block will concentrate on psychology, engineering and computing.

The building, which was given an “excellent” rating by the Building Research Establishment, boasts new features including a child development laboratory, as well as some of the world’s most sought-after science equipment, costing a total of £10 million. The huge investment coincides with a surge in popularity in courses like biomedical science, whose graduates often progress into an NHS career.

Professor Ray Iles, assistant dean for the school of health and social sciences, said: “With the economic downturn upon us, postgraduates are coming to university with the goal of walking into a career at the end of it. They are turning their back on the arts and coming back to science.

“What we have here is the best equipment, the best lecturers — we can compete with anybody.

“It is a growing industry and we have put ourselves near the forefront. When people research science courses, they will look at these facilities and realise this is the place to be.”

The new facilities have created room for the university to expand its Masters degrees and PhD programmes in bioanalytical sciences, which will see an abundance of new research emerge from the campus.

It was these plans of expansion that led Professor Iles and his team to wave goodbye to leading medical school St Bartholomew’s in 2004 and join Middlesex.

With a boyish smile he admits that when he thinks of the level of equipment at his disposal he has to pinch himself.

“This is the stuff dreams are made of, it doesn’t get any better than this. There is nothing we cannot do.”

He points to one particular piece of equipment he affectionately refers to as “his baby”. The £700,000 mass spectrometer allows detailed information about a specific sample to be collected.

And despite its hefty price tag, Professor Iles insists the machine is not off limits to undergraduates.

He explains: “It is not enough to write on your CV, ‘I can operate this’. Employers want to know you actually used the machine. They want you to have real skills.”

It is this concept of career-ready teaching that is the ethos of the science school.

The biggest lab used for lectures in the building holds 60 pupils, but Professor Iles said the aim was not to fill it, but to provide more one-to-one teaching.

He said: “We never wanted huge lecture rooms. We need to see what students are doing, making sure they are doing it the right way. That’s why we enjoy having lectures in rooms right next to the labs.

“If we’re teaching and then all of a sudden we want to explain what we’re talking about, we can just nip next door and do the experiment.

“We need to provide students with not just the theory, but also vital lab skills — graduates who can walk straight into a lab and get things done.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here