Freddie Knoller wanted adventure. He wanted to see the bright lights of Paris, the Moulin Rouge and the naughty girls he had read about in books.

But occupied Paris showed him a side of his beloved city that was darker than he could ever have imagined. He fled, and his journey through wartime Europe eventually to him to the gates of Auschwitz, and then onwards, witnessing betrayal, inhuman cruelty and mass murder.

Freddie, who now lives in Totteridge, was born in Vienna to Jewish parents, who paid a guide to help him escape to Belgium when he was just 17.

From there, he could have caught a boat to take him to safety in England, but he refused to give up on his dream of seeing Paris.

But before he could reach the French capital, he was arrested and thrown into a concentration camp in Saint-Cyprian, on the French border.

“There was no food. People were dying of cholera and typhoid and I wanted to live,” he says, bluntly. And so one night, Freddie slipped past the guards, ducked under some barbed wire and escaped.

Mr Knoller dips in and out of perfect French as he continues his story, of how he ended up in the French town of Gaillac, where he found work on a farm with his cousins.

When he had saved 100 Francs, he bought himself a new identity and Robert Metzner, from Alsace-Lorraine, was born. Freddie Knoller, to all intents and purposes, was dead.

So off he went. People told him he was mad as the Germans had occupied Paris but undeterred by war, he didn’t listen.

And when he arrived at Montmartre, La Place Pigalle was everything he hoped it would be. “If my father would have seen me, he would have smacked me”, he laughs.

The young man befriended a Greek named Christo who introduced him to owners of night clubs, cabarets and brothels. His job was to introduce the Nazi soldiers to the prostitutes.

He said: “I’ve been referred to as a pimp in Nazi Paris, but I was so detached from the situation that what I was doing didn’t occur to me.”

This came to an abrupt end when he was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo.

He said: “I’m not ashamed to say I wet myself. I was so scared they’d find out I was Jewish.”

Fortunately, they didn’t. Instead, the Nazis offered him a job as a German interpreter and that was when the reality of the war set in. Freddie escaped to the mountains of Figeac, joined the resistance and fell in love with a French girl named Jacqueline.

He said: “I was elated to be fighting my enemies instead of earning money from them.”

But his relief was short lived. He broke up with Jacqueline, who had terrible mood swings, and – “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned,” he says - she betrayed him to the Nazis.

The next day he was arrested. His captors burned him with cigarette butts and smacked him until he bled. When he could not take it anymore, he told them who he really was.

He said: “I was sent to a transit camp in Drancy until I was deported on October 6, 1943. We were thrown into cattle wagons, squeezed in like sardines.

“We weren’t given food or drink. We had to share a single bucket for the toilet. People died.”

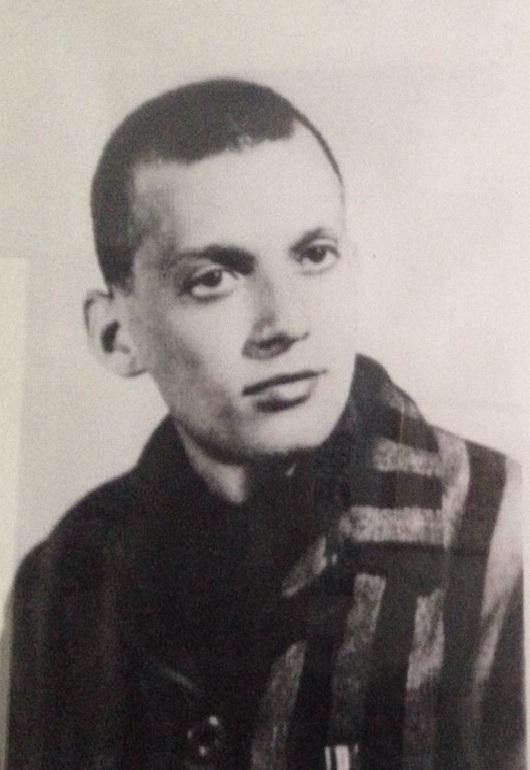

When Freddie got off the train, he was greeted with the now infamous sign “Arbeit macht frei” - work gives you freedom. His hair was shaved, a number was tattooed on his arm and was given a pair of striped pyjamas. He was frightened.

Mr Knoller said: “A soldier told us people had been gassed and cremated. It was the first time we’d heard such a thing. We couldn’t believe it. Germany was such a cultured country.

“One of the soldiers told us that soon, we’d smell a sweet smell in the air and that was the bodies burning. Quite soon we did smell it but to us, it wasn’t sweet.”

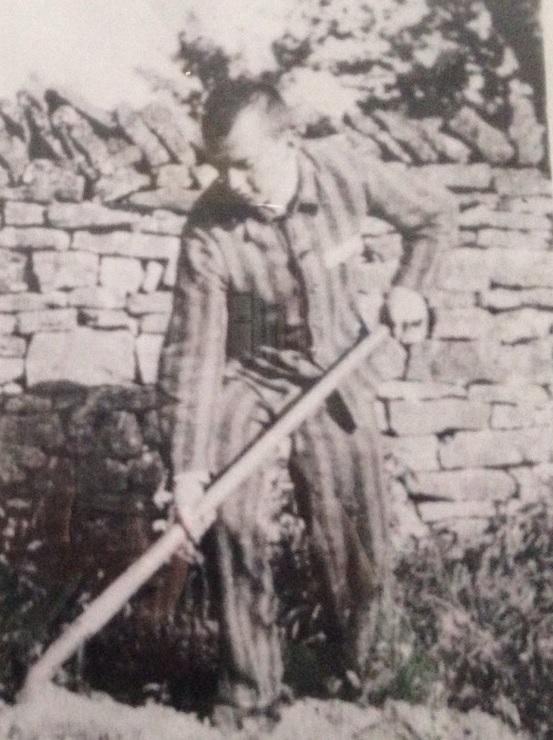

Every day, Freddie had to carry 25kg sacks of cement on his shoulder. He said: “If we didn’t run fast enough, we were whipped. Those who collapsed were taken away and we never saw them again.”

The only sustenance prisoners were given was a mug of coffee, a slice of bread and two watery bowls of soup each day.

He pauses for a moment, hesitating. “Our only thought was for our own survival. I am so ashamed to say this, but I saw one of my campmates tucking bread under his bed and I stole it.”

Then in 1944, rumours of the D-Day landings began to spread. This gave them hope, but they did not help them survive. In January 1945, Auschwitz was evacuated and the prisoners were forced to walk miles and miles as temperatures plunged to minus 25. It was one of the death marches in which thousands died. Those who were too weak to continue were shot.

Mr Knoller said: “In the morning we were woken up by the Germans shouting but the guy next to me didn’t move and I saw he was dead. He was a middle-aged political prisoner because he had a red triangle.

“I ripped it off and sewed it onto my uniform because they were better treated. One day we were making rockets and we decided to sabotage it by putting sand into the machinery."

But the Germans realised the political prisoners’ ruse, and in retaliation took 50 Jews and lined them up against the wall.

Mr Knoller said: “They put ropes around them and strangled them and made us watch. It took 15 minutes for each to die.”

In March 1945, the prisoners arrived in Bergen-Belsen and Freddie was forced to dig through the earth to eat whatever he could find.

He said: “I saw young people finding sharp stones and ripping off the flesh of the dead people to roast and eat. I couldn’t do it myself.”

The camp was liberated on April 15, 1945 and the British army took the prisoners in, fed them and nursed them back to health.

When they ran out of food, the English soldiers asked for ten volunteers to help them loot a local farmer’s home.

He said: “I went, and in the kitchen of this farmhouse I found a large painting of Adolf Hitler in the corner. I picked it up and took a kitchen knife and slashed it in front of the farmer. I said, ‘you see what I am doing to your beautiful picture?’ The farmer spat at me.”

Although the war was over, the repercussions on Mr Knoller’s life could have been deadly. He was sent to recuperate - ironically, in his beloved Paris, where a doctor took care of him.

He managed to trace his brothers, Otto and Erich, and joined them in America where he met his English wife, Freda. The two have been happily married since 1963, have two daughters and one grandson.

He is also a regular user of the Holocaust Survivors Centre in Golders Green, which supports those who lived through the genocide.

“One last thing”, he said, as I turned to leave. “I haven’t shown you this.”

He rolls up his sleeve to reveal his tattoo, a bitter blue. 157108.

“It’s a part of me, wherever I go.”

Freddie Knoller's War will be aired on BBC2 on Thursday, January 22 at 9.30pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel